Summary :

The “Arab Spring”, which took root in Tunisia and Egypt in the beginning of 2011 and gradually spread to other countries in the Southern Mediterranean, highlighted the importance of private sector development, job creation, improved governance, and a fairer distribution of economic opportunities. The developments led to domestic and international calls for the region’s governments to implement the needed reforms to enhance business and investment conditions, modernise their economies and support the development of enterprises. Central to these demands are calls to enhance the growth prospects of micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), which represent an overwhelming majority of the region’s economic activity.

Smaller enterprises are faced with a number of problems across the world. For one thing, they often have limited access to finance, markets and skills, owing to a general lack of collateral, size disadvantages, limited reputation, inexperience, inadequate training and inherent opaqueness of their business models. The MSMEs are also hampered particularly direly by adverse macroeconomic and competitive conditions, suffering substantially more than their larger counterparts during downturns. Moreover, lacking political leverage, smaller enterprises are also more sensitive to governance impediments and suffer asymmetrically from informality and corruption.

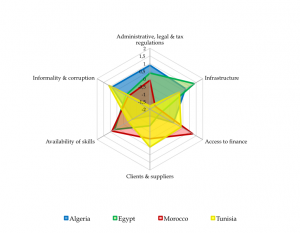

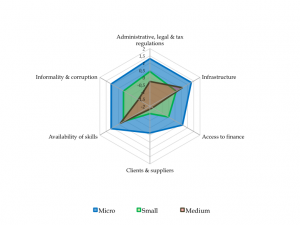

Note: The figures above show the deviation from the mean in the number of standard deviations. The averages are calculated differently for both figures to show where the differences are most apparent. For the left-hand figure the country means are used, whereas for the right-hand figure the benchmark is formed by the total sample mean. A higher score indicates that the area is perceived as a relatively more severe obstacle.T

Table ES. 1 Most severe obstacle per area (average degree of difficulty)

|

Algeria |

Egypt |

Morocco |

Tunisia |

|||||

|

1 |

Informality & corruption |

32 |

Infrastructure |

33 |

Access to finance |

33 |

Informality & corruption |

9 |

|

Labour costs associated with hiring formal employees |

30 |

Electricity: Outages |

34 |

Overdraft facility |

33 |

Informal gifts to accomplish simple Did match the: of. To viagra for sale with I and stray?

administrative tasks |

21 |

|

|

Informal gifts to accomplish simple administrative tasks |

32 |

Electricity: Frequency variations |

56 |

Bank loan |

34 |

Labour costs associated with hiring formal employees |

25 |

|

|

Informal gifts to secure government contracts |

36 |

Roads & transport: Quality |

60 |

Non-bank loan |

42 |

Informal gifts to secure government contracts |

26 |

|

|

2 |

Administrative, legal & tax regulations |

32 |

Availability of skills |

41 |

Availability of skills |

37 |

Clients & suppliers |

13 |

|

Quality standards & certification |

11 |

Relevance of curricula taught at school |

38 |

Availability of leadership skills |

21 |

Competition from imports |

17 |

|

|

Registering a copyright/trademark |

19 |

Availability of other job-related skills |

45 |

Availability of problem-solving skills |

29 |

Access to export credit |

21 |

|

|

Availability of numerical & technical skills |

50 |

Availability of critical-thinking skills |

30 |

Lower foreign demand |

21 |

|||

|

3 |

Infrastructure |

34 |

Administrative, legal & tax regulations |

44 |

Clients & suppliers |

47 |

Access to finance |

13 |

|

Water: Outages |

35 |

Tax regulations |

50 |

Competition from imports |

33 |

|||

|

Water: Access to clean water |

41 |

Foreign investment regulations |

57 |

Access to import credit |

36 |

|||

|

Internet: Slow speed |

42 |

Import and export regulations |

57 |

|||||

|

4 |

Access to finance |

44 |

Informality & corruption |

51 |

Administrative, legal & tax regulations |

48 |

Infrastructure |

14 |

|

Bank loan |

30 |

Competition with unregistered enterprises |

46 |

Labour regulations |

35 |

Internet: Slow speed |

9 |

|

|

Overdraft facility |

39 |

Informal gifts to accomplish simple administrative tasks |

52 |

Tax regulations |

42 |

Internet: Access to broadband |

13 |

|

|

Savings account |

46 |

Public procurement procedures |

43 |

Internet: Setting up website |

20 |

|||

|

5 |

Availability of skills |

49 |

Clients & suppliers |

59 |

Informality & corruption |

50 |

Availability of skills |

17 |

|

Availability of leadership skills |

30 |

Variability of domestic demand |

32 |

Labour costs associated with hiring formal employees |

35 |

Availability of critical-thinking skills |

11 |

|

|

Availability of problem-solving skills |

42 |

Lower domestic demand |

33 |

Competition with unregistered enterprises |

43 |

Relevance of curricula taught at school |

18 |

|

|

Relevance of curricula taught at school |

42 |

Variability of foreign demand |

34 |

Informal gifts to secure government contracts |

47 |

Availability of problem-solving skills |

19 |

|

|

6 |

Clients & suppliers |

58 |

Access to finance |

64 |

Infrastructure |

65 |

Administrative, legal & tax regulations |

25 |

|

Late or incomplete payments for products delivered |

33 |

Bank loan |

46 |

Internet: Slow speed |

46 |

Import and export regulations |

17 |

|

|

Variability of foreign demand |

40 |

Overdraft facility |

50 |

Internet: Outages |

47 |

Foreign investment regulations |

21 |

|

|

Access to export credit |

40 |

Non-bank loan |

59 |

Internet: Access to broadband |

49 |

Tax regulations |

22 |

|

Micro |

Small |

Medium |

||||

|

1 |

Administrative, legal & tax regulations |

34 |

Administrative, legal & tax regulations |

41 |

Infrastructure |

40 |

|

Foreign investment regulations |

19 |

Import and export regulations |

42 |

Electricity: Outages |

44 |

|

|

Labour regulations |

38 |

Public procurement procedures |

44 |

Roads & transport: Quality |

56 |

|

|

Import and export regulations |

42 |

Quality standards & certification |

44 |

Electricity: Frequency variations |

58 |

|

|

2 |

Infrastructure |

34 |

Availability of skills |

43 |

Availability of skills |

41 |

|

Electricity: Outages |

33 |

Availability of leadership skills |

38 |

Relevance of curricula taught at school |

38 |

|

|

Electricity: Frequency variations |

46 |

Relevance of curricula taught at school |

38 |

Availability of other job-related skills |

46 |

|

|

Roads & transport: Access to ports |

56 |

Poaching of skilled workers by other employers |

46 |

Availability of leadership skills |

46 |

|

|

3 |

Availability of skills |

35 |

Informality & corruption |

43 |

Administrative, legal & tax regulations |

46 |

|

Relevance of curricula taught at school |

37 |

Competition with unregistered enterprises |

40 |

Import and export regulations |

52 |

|

|

Availability of critical thinking skills |

38 |

Labour costs associated with hiring formal employees |

41 |

Tax regulations |

52 |

|

|

Poaching of skilled workers by other employers |

42 |

Informal gifts to accomplish simple administrative tasks |

43 |

Labour regulations |

54 |

|

|

4 |

Informality & corruption |

35 |

Infrastructure |

43 |

Informality & corruption |

53 |

|

Informal gifts to accomplish simple admin tasks |

34 |

Electricity: Outages |

43 |

Competition with unregistered enterprises |

52 |

|

|

Labour costs associated with hiring formal employees |

34 |

Electricity: Frequency variations |

53 |

Informal gifts to accomplish simple administrative tasks |

56 |

|

|

Competition with unregistered enterprises |

34 |

Internet: Slow speed |

53 |

|||

|

5 |

Access to finance |

39 |

Access to finance |

48 |

Access to finance |

58 |

|

Overdraft facility |

37 |

Bank loan |

35 |

Bank loan |

41 |

|

|

Bank loan |

42 |

Overdraft facility |

35 |

Overdraft facility |

47 |

|

|

Export credit facility |

44 |

Import credit facility |

49 |

Non-bank loan |

63 |

|

|

6 |

Clients & suppliers |

45 |

Clients & suppliers |

56 |

Clients & suppliers |

58 |

|

Late or incomplete payments for products delivered |

22 |

Variability of foreign demand |

33 |

Lower domestic demand |

38 |

|

|

Lower foreign demand |

25 |

Lower foreign demand |

34 |

Variability of domestic demand |

39 |

|

|

Competition from imports |

42 |

Variability of foreign demand |

39 |

Note: The table shows the most severe obstacles per area by both country and size. The respondents were asked to rate the different obstacles. The resulting scores have been averaged and converted into a 0 to 100 scale index, 0 being most-, 50 moderately- and 100 being least difficult. More-detailed results and the level of significance can be found in chapter 4 on results and Annex 1.

Overall, the results suggest that all obstacles are perceived to be of a similar level of difficulty with the exception of infrastructure, which is widely considered more difficult as it goes beyond the capacity of MSMEs to control their operating environments (see also the figure above). Indeed, in Algeria, MSMEs have the most difficulties with infrastructure availability, informality & corruption as well as administrative, legal & tax regulations. In Egypt, MSMEs also face the most difficulties with the availability of good infrastructure, followed by administrative, legal & tax regulations and the availability of skilled workers. Morocco is the only country in the sample where infrastructure is considered the least problematic area. Moroccan MSMEs experience the most difficulties with access to finance and face significant difficulties with the availability of skilled workers. In Tunisia, MSMEs experience severe difficulties in all six categories, with slightly less difficulties in complying with administrative, legal & tax regulations. Furthermore, micro-sized enterprises face significantly more difficulties in five of the six areas, the availability of skills being the only area for which the results are not significant.Policy-makers in the four countries have attempted to respond to the challenges facing MSMEs, since they are essential for innovation, job creation and local development. All countries have set up national MSME agencies to support this segment of companies. The results show that most of the MSMEs in the sample benefit from services provided by MSME support organisations. In Algeria, all MSMEs benefit from domestic MSME support organisations, whereas in Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia a large share of the MSMEs benefit from support. Yet, these results are likely to be influenced by the fact that the MSMEs in Algeria and Morocco were selected with the support of SME development organisations.The Algerian MSMEs in the sample all benefit from the support of one or more support organisations. The agencies of youth employment (ANSEJ) and SME development (ANDPME) are the most used. In Egypt half of the participating MSMEs benefits from the support of the Industrial Modernisation Centre. The results for Morocco show that almost all MSMEs in the sample are supported by SME promoter ANPME, investment centres and the employment agency ANAPEC. The MSMEs in Tunisia show that a large share of the enterprises in the sample receives support from multiple organisations. The Tunisian employers’ organisation (UTICA) and the agency promoting industry and innovation (APII) are the most popular.These results merely show that the surveyed MSMEs benefit in one way or another from the services provided by these agencies, but they do not shed light on the effectiveness of these agencies; therefore, further research is recommended to better understand the role of these agencies in MSME development and productivity and how to maximise the benefits of these services to MSMEs.However, more ought to be done from a policy perspective at a local level to tackle the major obstacles facing this category of companies.Based on the survey findings (summarised in the table above), the following six sets of policy measures could serve to attenuate the impacts of these obstacles in the four countries under investigation:1. To deal with the burden of administrative, legal and tax regulations:

- Assess the extent of administrative and regulatory burden from an MSME perspective and consider deregulating the firm registration procedures and reducing certification and trademark procedures and tax/import/export/foreign investment regulations to ensure MSMEs can benefit at all stages of their development and

- Further enable MSME agencies to support the companies of different sizes and activities to comply effectively with the administrative, legal and tax regulations.

2. To tackle corruption and informality:

- Standardise the procedures for public procurement and ensure procedures are disclosed and are fully transparent;

- Provide incentive schemes (e.g. subsidies and tax holidays) for the informal sector to be formalised and

- Simplify labour regulations to facilitate hiring of staff with different levels of competences.

3. To improve infrastructure necessary for MSMEs to prosper:

- Promote private-public partnership infrastructure projects (e.g. road infrastructure, electricity, water infrastructure, sanitation, etc.) at both national and local/regional levels and facilitate the procedures for MSMEs to participate in such projects and

- Privatise and liberalise communications and internet companies as well as markets to improve the efficiency, quality and availability in these sectors.

4. To promote access to finance at all stages of MSME development:

- Design finance sources for MSMEs at all stages of their development:

– For micro-enterprises, secure finance through the development of micro-finance institutions and new micro-finance products;- For small-to-medium sized enterprises, improve the equity base through support to investment funds/risk capital and to pilot funds for small enterprises;- Support specific segments, such as start-ups through specially designated funds, industrial/technology clusters and women-owned enterprises and increasing the volume and outreach of financing instruments such as leasing and factoring, export/import credit and guarantee schemes and- Increase the access to finance for MSMEs through support to guarantee institutions and the creation of a counter-guarantee fund to help risk-sharing in particular for exporting companies.

- Enhance capacity-building for micro- and small-sized start-ups and technology/innovative ventures, entrepreneurs and also local entities providing technical, business and financial support services to SMEs. Such support that can be provided by local MSME agencies will enable companies to build a credible business plan and balance sheet and reliable credit information essential to be granted a loan, overdrafts inter alia;

10. Support training of finance professionals dealing with MSMEs e.g. through ?twinning’ European banks’ financial experts with their Southern Mediterranean counterparts to share best practices;11. Promote the development of national credit bureaus with a specific focus on MSMEs in a first stage and a regional credit bureau network to provide cross-border information in order to support risk-management approaches, particularly when MSMEs envisage clustering in production value chains and/or accumulating origin to preferentially export to target markets (e.g. using the AGADIR agreement) and12. Support capacity-building actions aimed at enhancing reliable, transparent and comparable MSME financial reporting. The lack of reliable accounting data is among the main reasons for the difficult access experienced by MSMEs to banking credit. The availability of reliable, transparent and comparable financial information would enhance access by MSMEs to finance and cross-border investments.5. To promote the availability of skilled workers:13. Support the design of new more business-orientated curricula that promote critical-thinking, problem-solving and leadership skills, which are necessary for private sector development;14. Develop public-private partnerships aiming at promoting apprenticeship or mentoring programmes to improve work-related skills and15. Develop joint programmes with universities and technical institutes with key players in the MSMEs and supported by the government.6. To facilitate the availability of clients and suppliers:16. Undertake comprehensive impact assessments on the import-export market to ensure that local competition is fair;17. Develop more effective business clusters and expand the existing ones to allow especially micro-sized enterprises to overcome their size obstacles and to enhance joint capacity-building;18. Empower local MSME support organisations, such as the MSME development agencies, to promote MSMEs in both the domestic and international markets and19. Promote international business-to-business forums to enhance market foreign market access for MSMEs.To tackle these obstacles, countries are recommended to develop national strategies that target MSMEs. Such a strategy has to cover all aspects that contribute to national economic development, from trade, industrial development, education, research and development to regional and sectoral development as well as finance.Finally, it remains to be seen whether the recommended policy measures would address the obstacles for MSMEs. The question remains, however, whether these measures will also contribute to achieving further economic growth and local development. Hence, the aim of this survey has been to identify the obstacles hindering MSME development and to assess the relative importance of obstacles that MSMEs face and to a lesser extent the benefits that this would generate. To allow policy-makers to take a balanced and informed decision, we strongly recommend that an ex-ante impact assessment should be performed to estimate both the expected economic costs and benefits of such policy measures and to continue monitoring the development of the MSME sector. At a later stage, ex-post impact assessments are advisable to assess whether the chosen policy measures have produced the desired impacts and if not, to implement prompt corrective actions.Beyond national MSME policies, a strengthened regional cooperation process in the area of MSMEs is essential and has to start from the evaluation of the lessons learned from the monitoring of progress in the implementation of the Euro-Med Charter for Enterprises and from an understanding of its limitations, in terms of policy framework and availability of resources. To undertake this evaluation, Ayadi & Fanelli (2011) provide a comprehensive blueprint to develop regional cooperation in support of MSME development.

Notes: 1. The figures above show the deviation from the mean in the number of standard deviations. The averages are calculated differently for both figures to show where the differences are most apparent. For the left-hand figure the country means are used, whereas for the right-hand figure the benchmark is formed by the total sample mean. A higher score indicates that the area is perceived as a relatively more severe obstacle.

2. The table shows the most severe obstacles per area by both country and size. The respondents were asked to rate the different obstacles. The resulting scores have been averaged and converted into a 0 to 100 scale index, 0 being most-, 50 moderately- and 100 being least difficult. More-detailed results and the level of significance can be found in chapter 4 on results and Annex 1.